Rolf's Pork Store

In the old days, Germans were everywhere in Albany. There were German bakeries, saloons, churches, markets, and farms growing cabbages. German language newspapers, German singing societies and social clubs, and even a German gun club. All of that is gone now, forgotten or Anglicized. But one piece of old German-Albany lives.

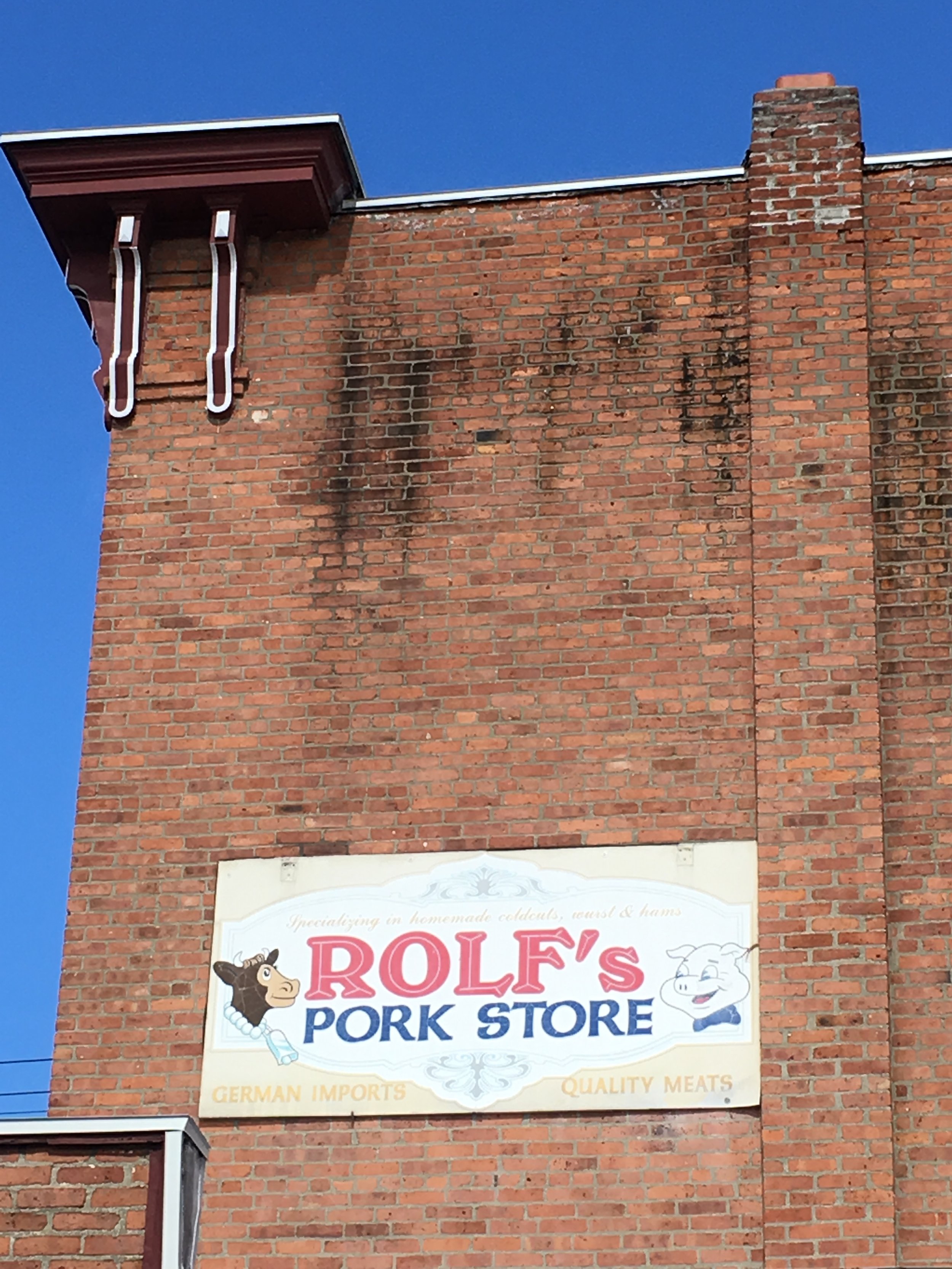

Rolf's Pork Store is in a brick building occupying a corner lot on Lexington Avenue, originally Snipe Street, first settled by the Dutch in 1614, it is one of the oldest public thoroughfares in one of the oldest places in America. The store has been doing business as a German market and specialties shop since 1868 -- chopping, grinding, and smoking meats, making hams, chops, bacon, steaks, sausages and more. The meat arrives, mostly from Nebraska nowadays, and is turned into delicious food products by Glen Eggelhoefer and his staff, all of whom are related.

Rolf's is a time machine. The past and present commingle in a centuries old building whose hub is the multistory, wood fired smoker used to cook and cure the meats since the beginning. Hardwood chips smolder in the basement, rising slowly through the smoke room for hours and vented through an old chimney. The process varies depending on what's being made, but the end result is uniformly excellent.

Rolf's does not advertise and is barely online. It relies solely on very loyal customers. Rolf-lovers span generations and drive in from all over because of the unique offerings and the undisputed quality. "Plus new customers, of course," Glen says. He says those who come into the store are a broad cross section, with a slight majority having family ties to Europeans "and the rest of them are Americans," including many with Caribbean or middle eastern family backgrounds. They come from Massachusetts, Vermont, the Mohawk Valley and the Lake George-Glens Falls region 75 miles north.

"I get a lot of everybody in here because we sell a lot of certain things that other people don't sell," he says.

Rolf's hasn't always been called by that name, but it's always been a meat market with German specialities. The store opened on what was then the city boundary shortly after the Civil War, with farms across the way. The store's debut followed the massive influx of immigrants to the U.S. from what is today Germany and was then a land riven by conflict and revolution By 1880, Albany had nearly 7,000 German residents, with the area where Rolf's is located called the Bowery (Dutch for farm) and Cabbagetown (so named for the German cabbages grown there)

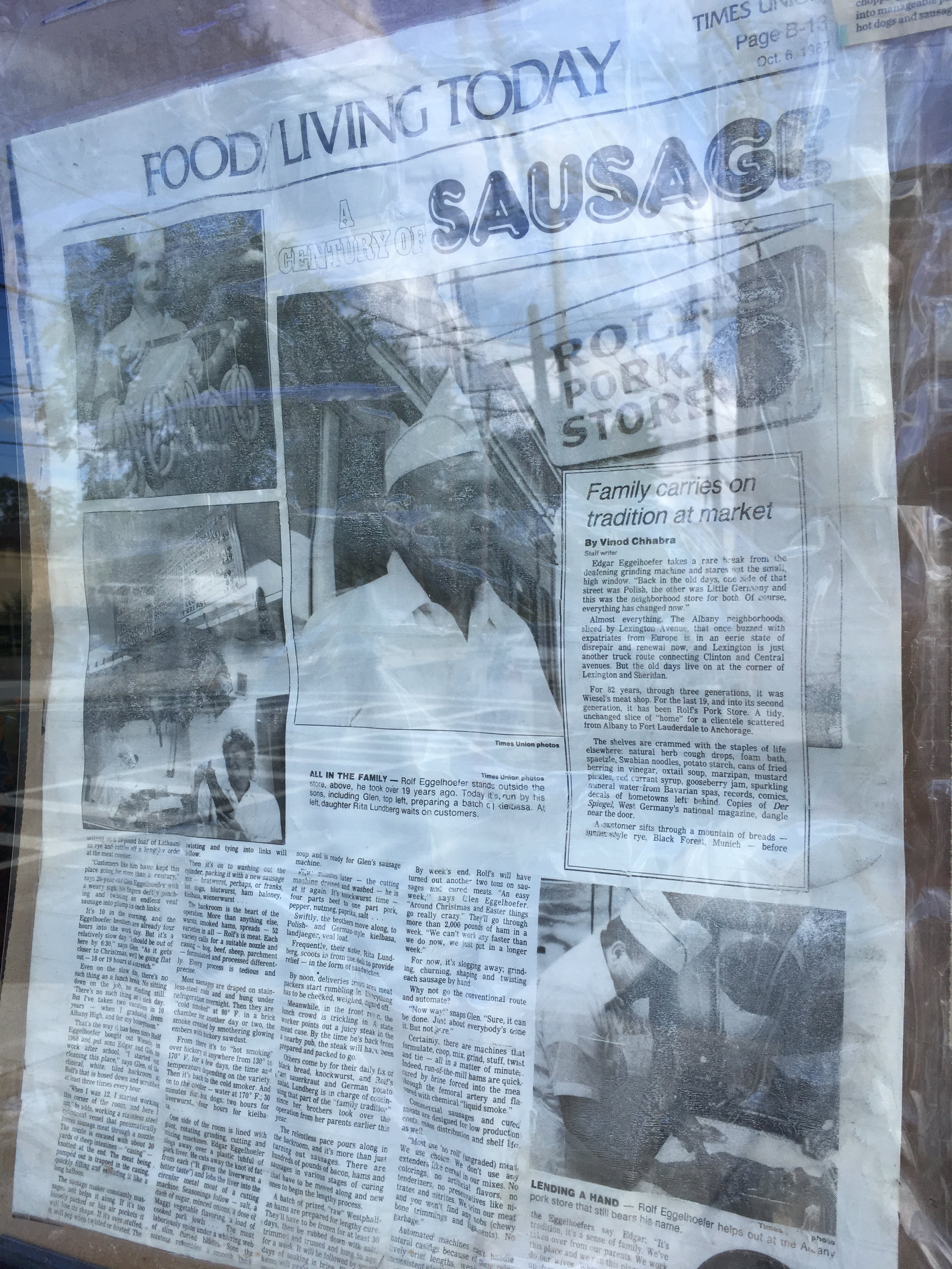

"We've been here, my family, for 53 years," Glen says. "The store has been here for 153 years." The original proprietors, the Weisel family, owned it for 90 years, followed by another family before Rolf purchased the business. Rolf immigrated to the U.S. in 1957 from Stuttgartt, Germany, where he was a "meister" butcher -- able to cut and process meats from hoof to table. A German meister "can take a walking animal and turn it into a hot dog," Glen says.

The shop makes more than 70 different products. It’s top sellers are smoked pork chops, bacon, frankfurters and bratwurst. And German hams fly out the door at Christmas time. Some of the rarer products include Lachsschinken, "salmon ham" sliced thin and served cold; Bauernschinken AKA "farmer's ham,"; Schinkinspeck, a bacon-like ham; and more recognizable names like daisy, black forest and the ubiquitous boneless smoked ham. There's also a wide assortment of wurst, sausages and kielbasa along with a full selection of fresh steaks, chops and choice cuts.

"We make all kinds of different blood sausages," Glen says. "I make a tongue blood sausage, I make a Thüringer that's shoulder meat blood sausage, I make a fat blood sausage, a kishka which is a barley blood sausage. So we make four different blood sausages." And seven different liverwursts and smoked salmon for the piscatores at the table.

Speciality products on demand include beef blood, sweetbreads, brains, hearts, kidneys, tongues and more. If you hunt, Rolf's will prepare and process your deboned venison. The same applies for customers wanting processing, preparation and vacuum packing of pork and mutton. Much of the demand is driven by the desire for all-natural products.

"No preservatives, no nitrates, no fillers, all natural smoke, no liquids, no colorings," Glen declares. standing below a menu sign guaranteeing the purity of "Rolf's own meats." The shelves and refrigerator cases are stocked with imported German products -- cheeses, beverages, jams, boxed mixes, snacks, greeting cards and more. "96 percent of everything in my store is German," Rolf says, with grocery items purchased by his wife during periodic trips to stock up in NYC.

"When we moved here in 1968, my building and up (the incline that rises west from the Hudson River) was Germans," Glen says. "My building on down was Polish. There was a Polish church, Polish school, and that's the way it was" before Albany's suburbs began to take shape in the 1960s, and families moved out and up in the world. "The Italians were over in the Delaware Avenue area and the Irish were everywhere else."

In those days, "there were a lot of us, now there's just me... In the 1970s there was probably a meat market on every other block. They were all over the place. But then they started building supermarkets."

Albany entered a traumatic period from the 1960s onward as old ethnic neighborhoods emptied out and their landmarks, stores and public places were abandoned or demolished. The Empire State Plaza rose up, Nelson Rockefeller's monument to himself and a spectacle of governmental power.

Critic Robert Hughes once called the plaza "the scariest monument I know .... the place would make Albert Speer seem delicate."

Albany city historian Tony Opalka says the impact of what was done in those years in the name of urban renewal is still felt. "A lot of what people would now like is gone and a lot of what's left is what no one wants."

But Rolf's still stands, now in its third century of hand-crafted production of the kind of quality food not easily found anymore. Glen and his now retired brother took over their father's business 33 years ago. From time to time, people arrive wanting to be trained in the kind of culinary craft practiced at Rolf's. "But they don't usually last very long. It's a lot of work and people don't like working so hard anymore these days," he says with a chuckle. But he's open to anyone who wants to learn and is willing to work.

Is the future of Rolf's selling products online like Harry & David, Fresh Direct, Instacart or the countless small businesses that sell regional BBQ and other craved specialties online? Perhaps. "I'm not a big computer guy, but that doesn't mean the kids won't do it when I'm gone," he said. For now, "I'm semi-retired and I work 50 hours a week, but I go away a lot. I have a very, very good crew."

Kyle Hughes is an independent journalist and the founder & publisher of NYSNYS News. He's at:www.NYSNYS.com

@nysnysnews

@saratogahistory